A Brief History Of The Montreal Metro's Fantastical, Shape-Shifting, Still Nonexistent Pink Line

Will it actually happen?

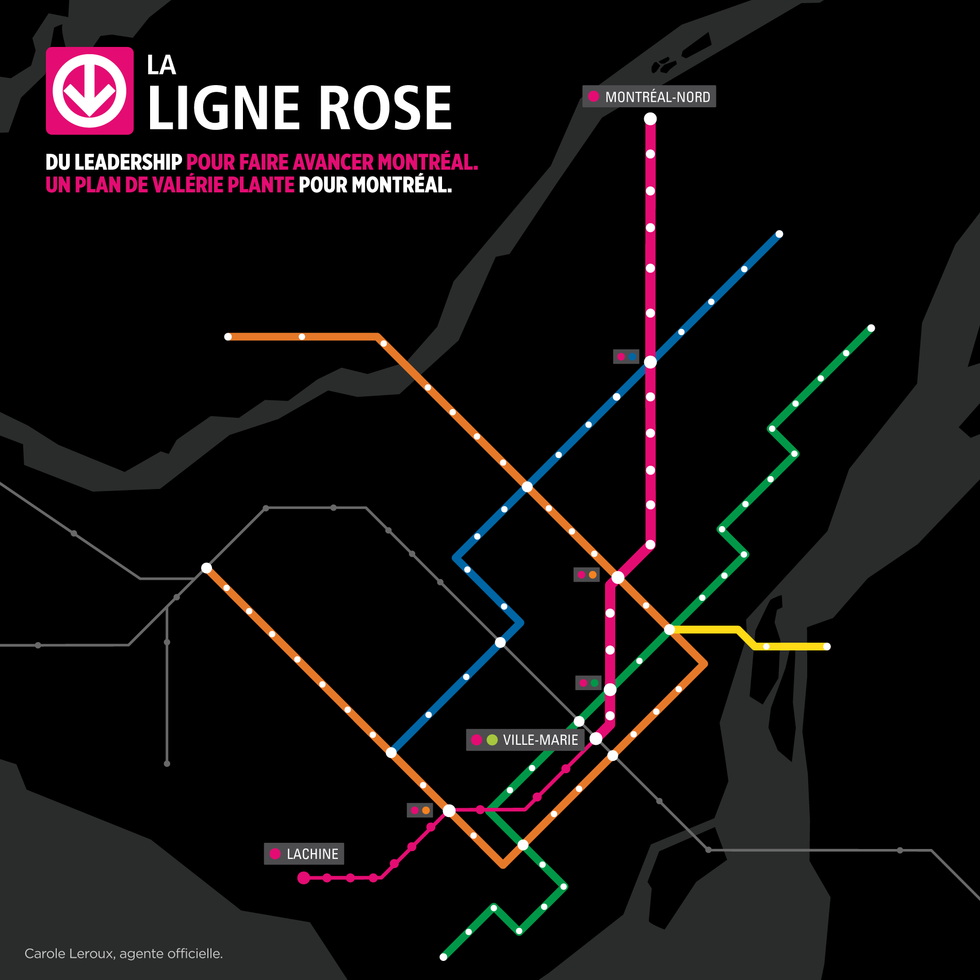

Projet Montréal's initial proposal for a pink metro line route.

A new "pink" Montreal metro line was supposed to one day provide new rapid transit between Montréal-Nord, downtown and Lachine. More than six years after Mayor Valérie Plante and her party, Projet Montréal, began campaigning on the proposal to radically expand the metro network, Plante says the project is beginning to take shape — though it hardly resembles the original plan.

Here's the recent history of the proposal, how it has changed and where it could go from here.

'Ambitious, bold and necessary'

Projet Montréal's initial proposal for a pink metro line route.

The pink line proposal was the cornerstone of Valérie Plante's first mayoral campaign in 2017. It has haunted her administration ever since.

She has called it an "ambitious, bold and necessary plan to increase Montrealers' mobility and, consequently, increase productivity and reduce inequalities."

Her party, Projet Montréal, has cited a need to reduce congestion on what it described as a sardine can-like orange line, which, pre-pandemic, was at or near capacity in some areas.

The pink line was to run north-south like the orange line, but through neighbourhoods that are underserved by rail, stretching from Lachine in the southwest to Montréal-Nord in the northeast, bypassing the crowded Berri-UQAM station with orange line connections at Vendôme and Mont-Royal, a green line connection at Place-des-Arts, and a blue line connection at the future station at the intersection of rue Jean-Talon and boulevard Pie-IX.

A preliminary map of the line showed an additional 27 stations in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Westmount, Ville-Marie, the Plateau-Mont-Royal, Rosemont–La-Petite-Patrie and Saint-Léonard.

The pink line was to take form in three phases, according to Projet Montréal: "a study and planning period, followed by a first construction phase to link Montréal-Nord to downtown, and an extension to Lachine."

Not so fast

The new metro line hit some bumps.

The appeal of a new Montreal metro line helped propel Plante into the mayor's office. But she quickly found herself at odds with the new provincial government.

The new governing party, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) had rejected the idea of a new metro line during the 2018 campaign. Instead, the party, including its leader, Premier François Legault, expressed favour for a transit project that would more directly benefit areas outside the City of Montreal (where the CAQ had won more National Assembly seats).

Plante vowed to push the project forward despite the CAQ's opposition. The city pursued a study on the pink line and, just weeks after the provincial election in October 2018, the mayor announced the creation of a six-person municipal office dedicated to the project.

The pink line, or something like it, also appeared to become more likely as the body that governs transit planning in the Montreal area, the Autorité régionale de transport métropolitain (ARTM), began its own evaluation of transit needs on Montreal Island. The ARTM resolved in May 2020 to propose ways to both relieve the eastern branch of the orange line and link the city's northeast, downtown and southwest through new "structuring public transport projects" — all goals of Projet Montréal's pink line.

From metro to tramway

A breakthrough came in June 2019, when the City of Montreal and Government of Quebec reached an agreement "in principle" to fund a tramway project between Lachine and downtown in exchange for the reallocation of other funds to build a tramway in Quebec City.

Plante declared victory, calling the project the "first section of the pink line," despite the earlier plan to begin with a downtown-to-Montréal-Nord segment.

Officials have been studying possible paths since. One 2021 proposal from the borough of Lachine called for a tramway stretching from 32e Avenue to the Atwater green line metro station via rues Victoria, Notre-Dame and Saint-Jacques.

The Lachine transit link proposal took more concrete form in a June 2023 plan for the development of the "écoquartier Lachine-Est," a 70-hectare former industrial site between the Lachine Canal and rue Victoria.

The plan calls for a direct connection between the new neighbourhood and the pink line, which the city describes as "a structured and efficient public transport network linking downtown to the Greater Sud-Ouest, including Lachine" — notably excluding the word tramway.

Reacting to the news, Plante nevertheless boasted the plan "sets the course for the development of the first section of the pink line."

A map of the écoquartier shows the line running on old right-of-way between rue Victoria and rue William-MacDonald with a station near 2e Avenue.

The REM de l'Est

Under the initial agreement between Quebec and Montreal, the Lachine tramway was supposed to — somehow, eventually — extend to a second tramway project in the East End, running along rue Notre-Dame.

In 2020, officials abandoned that idea in favour of the REM de l'Est, a new light-rail network akin to the under-construction Réseau express métropolitain (REM) between the South and North Shores, downtown and West Island.

The story of the REM de l'Est proved to be dramatic.

The network was to start at boulevard Robert-Bourassa downtown and use elevated tracks along boulevard René-Lévesque and Notre-Dame through Hochelaga-Maisonneuve before splitting into two branches, one going north to Montréal-Nord via Saint-Léonard and Rosemont–La-Petite-Patrie and the second continuing east to Pointe-aux-Trembles via Mercier and Montréal-Est.

Though Projet Montréal's initial pink line plan took a different route, Plante quickly branded the REM de l'Est the second pink line segment, saying it fulfilled her goal to create a rapid transit link between Montréal-Nord and Ville-Marie.

Fierce public opposition to the design of the light-rail network, especially to its elevated downtown portion, and a bad review from the ARTM eventually led REM de l'Est planner, CDPQ Infra, to drop the project, however. The governments of Montreal and Quebec stepped in to take over the planning of a new rail link in the East End, though it wasn't immediately clear what form or route it would take. Officials only committed to eliminating the downtown section and studying possible extensions north to Laval and east to Lanaudière.

Several proposals have emerged since then. One, from the urban development organizations Vivre en Ville and the Société de développement Angus (SDA), is almost identical to the original pink line plan, with two branches, from Montréal-Nord and Pointe-aux-Trembles, converging in Rosemont–La-Petite-Patrie before passing through the Plateau and downtown.

A second proposal from a coalition of metro-area mayors would have the REM de l'Est take a circuitous route between Mascouche and Repentigny via Laval, the East End, Montréal-Est and Pointe-aux-Trembles.

A group designated by the provincial and municipal governments is still working to determine the exact course of what they now call the "Eastern structuring project."

Will the pink line still be part of the Montreal metro system?

The "pink line" is looking less and less like the new metro line Plante and Projet Montréal proposed.

Over time, the mayor has distanced herself from the idea of an addition to the metro network and the project has become more figurative than literal.

"The pink line, whatever its name, colour or shape, is an idea that's beginning to take shape for the mobility and quality of life of people all over the island," the mayor explained following the first presentation of the REM de l'Est in December 2020.

She suggested the "pink line" could be any project or set of projects that realizes its three initial objectives: to bring rapid transit to underserved communities, to province better transit options in the southwestern pocket of the city and to relieve the orange line.

"In three years, our administration has succeeded in inscribing the whole of the pink line in the Government of Quebec's plans," she said in a 2020 video. "We intend to build on this momentum and offer more mobility options for Montrealers."